Martin Sherwin: I am in Cambridge, Massachusetts on April 26, 1982. Were you married when you were in Los Alamos?

Alice Kimball Smith: Yes. We had been married for twelve years.

Sherwin: I see. So you and your husband, Cyril Smith, went to Los Alamos and you were promptly put to work as a schoolteacher. Is that correct?

Kimball Smith: That is right, yes.

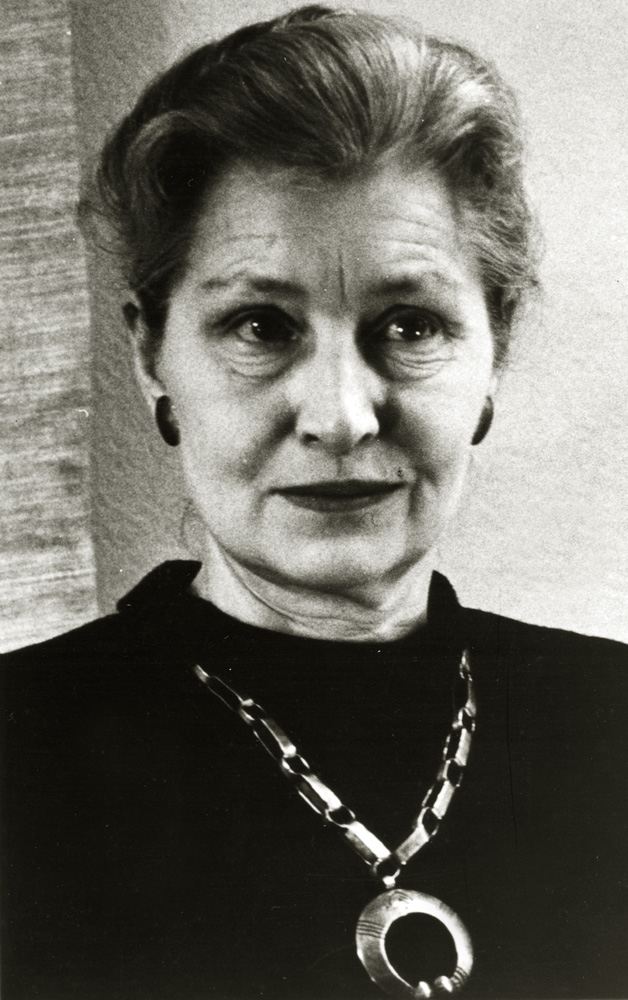

Sherwin: Okay. With that as general background, let me say that Alice Kimball Smith is a student of the history of the atomic bomb, and particularly the scientists’ reaction to it afterwards. She has written a book entitled A Peril and a Hope. More recently, she has been the co-editor of the letters of Robert Oppenheimer. Had you ever met Robert Oppenheimer before going to Los Alamos?

Kimball Smith: No. I had never heard of him, in fact, until I knew we were going to go there.

Sherwin: Can you remember when you first met him?

Kimball Smith: No, I do not remember. It must have been after I arrived in July of 1943. My husband had been there since April.

Sherwin: I am told that he was very much in evidence at Los Alamos. So you must have been able to see him repeatedly after you were there, despite the fact that you were not actually working on the project itself.

Kimball Smith: No, that is right. I had never set foot inside the Technical Area, but I did meet Oppenheimer frequently on social occasions, casually and informally.

Sherwin: How was your general impression of him?

Kimball Smith: I liked him very much. I found him helpful, thoughtful, and extraordinarily kind and pleasant.

Sherwin: He is often referred to as an extremely brilliant person. Did that come across in ordinary social contact?

Kimball Smith: I suppose it did. The place was full of so-called brilliant people, each one of them with their own special flavor. I do not know that that was the quality about Oppenheimer that struck me most. I supposed I was expecting someone slightly forbidding, and so was always pleased when he made nice personal gestures. I should say perhaps that my reaction may be quite different from that of people who had known him over the years, and seen him change from a rather eccentric young university professor.

Sherwin: You made a particular study of the reaction of the scientists to the making of the atomic bomb. I assume that Oppenheimer’s own reaction has been part of your study.

Kimball Smith: Yes, indeed it was. In fact, the title of the book – which does not tell very much about the contents unless one knows already, A Peril and a Hope – the phrase was taken from the talk that he gave at Los Alamos in his farewell speech to his colleagues there. Officially, this speech was given to the newly organized Association of Los Alamos Scientists. This was in mid-October of 1945 after he had resigned as director, but before he left.

He spoke then about the fact – which was greatly influenced by the thinking of his good friend Niels Bohr – that because in the release of atomic energy there lay such a great peril for the world, that there was perhaps a hope that nations would learn to live together. This speech, which is printed for the first time officially, except in private circulation at the time for Los Alamos, greatly influenced the thinking and the actions of his colleagues at Los Alamos.

Sherwin: When did Niels Bohr come? Toward the end of the project?

Kimball Smith: No, he was first there in December, 1943, which was only a few months after he had escaped from Denmark to Sweden and then to England. He came as a member of the British delegation, which was beginning to arrive. These British scientists were placed in various parts of the Manhattan Project. There was a group of about 15 or 20, some with their families, who came to Los Alamos over the next few months.

Sherwin: Did Bohr stay at Los Alamos for a long time?

Kimball Smith: He stayed for several weeks at a time. That is a very interesting and complicated story, to which Oppenheimer later gave me access before it had been generally circulated. Of course, he could not talk freely. He talked a great deal with Oppenheimer. He talked privately with a number of people. I remember a conversation in our own living room, which must have been toward the end of the war, with my husband and David Hawkins, in which Bohr was saying essentially the things that Oppenheimer later said. I did not know what the project was about, so these references were a little obscure to me.

Sherwin: Niels Bohr was pressing Oppenheimer in the directions of international control, or merely sensitizing him to the problems that were going to arise?

Kimball Smith: Both, I would say. But very definitely in the direction of international control of some kind.

Sherwin: Would Niels Bohr have been advocating a demonstration of the bomb rather than dropping it?

Kimball Smith: I have found no evidence that he expressed himself on this point, or that he ever said the bomb should not be used in Japan. I have looked for this in the things that he published and the things he said privately. I think it was probably because as a citizen of Denmark, he was hesitant to tell either England or the United States what they ought to do.

Sherwin: Oppenheimer himself was involved right up to the selection of possible targets for the bomb. Did he ever later express regrets that it had been dropped on a civilian or military target? I mean a city as opposed to just having a demonstration anywhere?

Kimball Smith: I cannot document my answer to this. In general, he never expressed regret. I won’t say never expressed regret; he never said it should not have been used under the circumstances. I am afraid I do not have a firm answer to whether he ever suggested there should have been a demonstration. It is my clear impression that, in retrospect, he thought there should have been. But in the context of the times, he understood so well his own reaction and that of his colleagues, and particularly that of Secretary of War [Henry L.] Stimson, whom he admired very much, that I think he never tried to revise history.

Sherwin: I suppose one should add that when you say that it was within the context of that time, that the bombs dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima were equivalent in their damage to what the regular bombing was doing, say, to Tokyo. The difference was simply that this happened in one instant, instead of with an armada of airplanes dropping tons and tons of chemical explosives.

Kimball Smith: That is certainly part of the answer. I, of course, feel very strongly that it is very hard, even for people who took part and lived through that period, to remember the uncertainties of the whole war, but certainly of the last year or two of it even after Germany had been defeated. There was very little real information available to people, even to scientists at Los Alamos, about the course of the war. Japan’s vulnerability was not recognized even by our own government, which had broken the Japanese code. There is again a whole chapter in this history about the strength of the peace party in Japan, which included the emperor, which was not recognized at all in the West. I think it is just terribly hard to recreate for people who did not live it, and even to remember for those of us who did, how strong this uncertainty and this fear of what the Japanese were capable of was.

Sherwin: I suppose many people thought that an armed invasion of the Japanese islands would be necessary. Seeing the bombs bring a speedy close to the war was seen with a great measure of relief. This must have been part of what transformed Oppenheimer into an overnight hero.

Kimball Smith: Yes. I think you are absolutely right about that. It is certainly in the official thinking in Washington. As it was conveyed to Oppenheimer and the other members of the Scientific Panel that was advising the War Department Interim Committee on atomic energy, this was a very strong factor.

Sherwin: How did it affect Oppenheimer himself to suddenly become such a public hero after living a rather secret life for those years at Los Alamos?

Kimball Smith: The life may have been a secret one for the public, but I think he had become accustomed to his position of leadership at Los Alamos and to the responsibilities that went with that. I think that the transition was a somewhat gradual one. One sees some of the uncertainties in his reactions to what he was going to do after the war. He kind of waffled about whether he was going back to Berkeley or going to Caltech. Eventually he did shift first to Caltech, back to Berkeley, and then very quickly went to the job in Princeton as the head of the Institute for Advanced Study. But his correspondence shows a great deal of uncertainty. He had ten or twelve tempting job offers, including Columbia and Harvard. For a while, he thought he would take Columbia. I think that his transition was marked by this kind of personal dilemma as to what he wanted to do after the war.

Sherwin: I would like to explore what one might call the evolution of conscience in Oppenheimer. Would you feel that this is markedly different before Los Alamos and after? Clearly, he had become a figure of much more responsibility afterwards.

Kimball Smith: Yes. I did not know him before, so I only know from hearsay and from reading his correspondence, which does not really deal with this central problem. We were unable, Charles Weiner and I, in editing the letters. Which, as you know, carry the story simply up through Los Alamos to the point where he did become a public figure, and saw himself as this rather than as a private one. There unfortunately does not survive any correspondence relating to his association with what are known as left-wing movements. The person to whom he would have written about this, his brother Frank, lived by 1936, when Robert’s interest in these social matters seem to have been aroused, not far away in California. So the two did not correspond.

We did not find any official correspondence with organizations. Whether this correspondence exists somewhere in the secret files of the government, I have no idea. But from what we did find, I should doubt it very much. For instance, his correspondence with Consumers Union, which was later put on the government blacklist of organizations, was very routine and showed a kind of token interest in what was going on and finding people to test products. But he was not always able to get to meetings.

Sherwin: I am astonished. Why was Consumers Union put on the blacklist?

Kimball Smith: I have forgotten the exact reason. Was one of its early directors later attacked by the House Un-American Activities Committee?

Sherwin: It is quite possible. I simply do not know.

Kimball Smith: It is interesting because it seems to us of course now a very middle of the road organization.

Sherwin: Were you at all in touch with him after the war? For instance, when there were the questions about the hydrogen bomb, the super, and then later on when the hearing took place for his security clearance?

Kimball Smith: I saw him occasionally during those years. He turned up; my husband was then at the University of Chicago after the war. I remember two or three occasions when he came. I did not see a great deal of him. My husband was a member of the first General Advisory Committee to the Atomic Energy Commission, which began to function on January 1, 1947. This was a very close-knit group. Cyril did not talk very freely about what went on there. But I certainly felt in touch indirectly with Oppenheimer during the next five or six years and occasionally thereafter.

Sherwin: Did he become more open after the hearings in his general response to the peril and the difficulties of things like the hydrogen bomb? Or do you think in the end he had pretty much gone along with building that?

Kimball Smith: No, I do not think he had. Well, he said he went along with it. Certainly that is clear in this statement that is so often quoted, when there seemed to be a technical breakthrough, that it was technically so sweet that one could not fail to pursue it. I frankly do not understand this. I never discussed it with him. I am sure there was an emotional revulsion to it. I know there was on the part of some people who had shared the initial negative decision with him. I did not see enough of him to speak firmly about that.

Sherwin: I think this gives me much of what I am interested in and can use. But perhaps you, just in thinking about it, would see some area that you would want to address, or think of something that I should have asked you but did not.

Kimball Smith: Well, about my personal reaction to Oppenheimer. As I say, I know it was different from that of people who had known him in the 1930s, of the wives of scientists who had entertained him in Berkeley. They had been so charmed by his nice manners, considerateness, and his arriving at any party with a bunch of flowers in his hand. And who were also somewhat disturbed by the marriage to Kitty, which had broken up another marriage. My husband and I – around 37, 38, 40 – were among the senior staff at Los Alamos. Some of the younger wives were a little more skeptical having known more of the background, which I learned only secondhand, about Oppenheimer and about his wife. But I did not share these reactions.

I remember particularly several very nice personal gestures. I do not know that I want this to be broadcast. But for instance, there was a tragic episode in the first autumn at Los Alamos when a young chemist, the wife of one of the group leaders, contracted some strange kind of polio that was not easily diagnosed. She died down in the government hospital outside of Santa Fe. This was very upsetting, of course, for personal reasons. We were particularly good friends with this couple. But also with all these children who gathered together on the Hill, and had brought a lot of germs from all parts of the country anyway.

I remember that Cyril and I went to see the husband as soon as he had come back from the hospital. At least we thought we had gone as soon as we decently could. As we approached his house, there was Oppenheimer stepping out of the darkness, coming back to speak with us. He had been there before anyone else. Saying, “I am so glad you have come. He needs you.” It was this kind of personal thing that struck me.

Then I remember when Niels Bohr arrived on the Hill. I had no idea who Niels Bohr was, to be perfectly frank, which sounds like abysmal ignorance now. I was not really familiar with the world of international physics since my husband was a metallurgist, and we had lived during the thirties near an industrial community in Connecticut. But I heard these references to “Uncle Nick” at some party quite early in the time he was there. Apparently, we were all involved in a discussion of international affairs. I cannot imagine what I said that made any kind of impression, but Oppenheimer spoke to me a day or two later and said, “Uncle Nick wanted to know who you are.” [Laughter] This was the kind of thoughtful thing that Oppenheimer did, you know. Being new to this whole community of scientists gave me a kind of personal lift.

Sherwin: Some of the people have described Oppenheimer in his later years as very arrogant. Does that come through in the correspondence, or in any of the contacts you would have had with him?

Kimball Smith: Certainly not in my personal contact. But then I was not really doing business with him. I should say that toward the latter part of the Los Alamos period, when things picked up in intensity, that one saw less of him at parties. He and Kitty had a great deal of official entertaining to do of the consultants like [James B.] Conant, Richard Tolman, and [Isidor] Rabi who came to the Hill, not to mention General Groves. But I had no personal association with his arrogance at all.

Another instance of his helpfulness was when I was writing the book about the atomic scientist movement. This must have been in 1963, when I thought the book had just gone to the University of Chicago Press in its final form – the manuscript, rather. My husband and I happened to be in Princeton and saw Kitty and Robert. He said, “You know, I have some material about Niels Bohr. His own papers about his attempts to get [Winston] Churchill and [Franklin D.] Roosevelt to talk to [Joseph] Stalin about the bomb before the end of the war, and I would like you to see these.” The only other person he had shown them to was the historian Herbert Feis. So I went back to Princeton in a week or two, spent a day looking over those papers, and was able to use the material in the book. This was an instance of great helpfulness that was not necessary.

Sherwin: Well, you have chronicled the general movement of the scientists in how they were coping with the bomb as a new force on the international scene. What kind of role did Oppenheimer himself play in that story?

Kimball Smith: This, I think, is a very interesting point to address. There was already at Los Alamos, when he made this speech I mentioned, a flourishing organization of scientists who were concerned about international control. The idea did not come entirely or directly from Oppenheimer. It was very much in the air. It partly originated in activities at the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago, and the group there that had tried to press the government to demonstrate the bomb rather than drop it on Japan without warning.

Sherwin: After the war, did Oppenheimer join in with any of the groups?

Kimball Smith: As soon as he resigned from Los Alamos, he became a member of the Association of Los Alamos Scientists. By that time, there was forming in Washington a loose federation of atomic scientists, which within a few months, by January of 1946, expanded into the Association of American Scientists to include people who had not worked directly on the Manhattan Project. Oppenheimer felt that he already, as early as late May of 1945, had been called in as an advisor to the government. He felt that he could not take an active part. He was busy, extremely busy. But he remained throughout the next year or two a kind of quiet, private advisor to the young men who began to direct the Washington organization. So he was very much in evidence, but only in the internal workings of it.

Sherwin: All right.

Kimball Smith: He did make public statements during this period. But he was unfamiliar with this role of private advisor. I suspect it impressed him. He found Henry Stimson, the Secretary of War, to be a very congenial and impressive person, as I think most people did who worked with Stimson. Stimson had adopted the idea of international control during the war.

He had adopted it, as many people have not realized, from Vannevar Bush and James Conant, who were at the head of the technical part of the Manhattan Project. They were the ones who had really introduced the idea into official thinking. So Oppenheimer felt his responsibility as an advisor as early as that, and so was rather guarded in what he said publicly. He did testify before congressional committees, but always in this kind of dual role as scientist and advisor.